This year was expected to be a rough one for employers, following predictions of a coming tidal wave of costly employee lawsuits and labor complaints powered by the COVID-19 pandemic and last year’s racial justice protests.

So far, though, that onslaught of litigation hasn’t materialized. Why not? Partly because the pandemic itself closed courts for months last year in Virginia, so there is a backlog of litigation to work through, say employment attorneys. And lawyers for employers and employees are waiting to see how the courts rule in any active employment-related lawsuits to help them figure out legal strategies. Plus, there are new state and federal laws to sort out.

A wave is likely still coming, though, say employment attorneys, so businesses shouldn’t let their guard down. “While the sky is not falling, I still think there’s a lot of risk for employers,” says Todd Leeson, a partner at Roanoke-based Gentry Locke Attorneys.

For one thing, many employers have gone from offering incentives for vaccinations to mandating that their employees get vaccinated. And while courts have generally been upholding an employer’s right to issue employee vaccination mandates, Leeson says, there are legitimate exceptions that can be carved out for health issues and religious beliefs and that can create some room for disputes around a hot button issue that can trigger strong emotions.

“I do think the folks who are not vaccinated who perceive that they’re being singled out unfairly are going to challenge that if they end up getting fired,” says Leeson, who represents companies and employers in labor and employment cases.

Another reason businesses haven’t yet seen the predicted wave of litigation is Virginia’s particular business and legal culture, says Alexandra Cunningham, a Richmond-based partner with Hunton Andrews Kurth, who co-heads the firm’s products liability and mass tort litigation practice group. Virginia juries generally aren’t that tort-friendly, she says, and the state’s purple-shaded politics means less chance of conflict between courts and state policymakers. Virginia also has a less vulnerable workforce than other states, offering more white collar jobs that allowed work-from-home options, she says.

“I also think frankly we had a pretty strong [state] response to the virus, so we don’t have some of the issues that states like New York had,” she says, adding that better control over the pandemic generally means fewer lawsuits. “And we were late to have a surge and the guidance was already in place.”

According to a national database maintained by Hunton Andrews Kurth that tracks state and federal litigation involving COVID-19 claims, the most litigious state, California, had 2,018 pandemic-related legal complaints from January 2020 through July 2021. New York was second, with 1,743 pieces of litigation. During the same period, Virginia tallied just 135 pandemic-related complaints.

Even nationwide, the pandemic litigation count shows no surge in 2021, according to the Hunton database. Nationwide last year there were 7,734 lawsuits related to the pandemic. Through July of this year, there are 3,767 complaints.

Nevertheless, employment attorneys say they haven’t lacked for work amid the pandemic. “Firms have been incredibly busy over the past year,” Cunningham says. “Like the rest of the world, businesses have had to drink from a fire hose to figure out the obligations they have to respond to [in regards to] protecting employees and following mandates — especially at the [pandemic’s] beginning, when those mandates were changing constantly.”

Expected boom is quiet

A major development for employers is the Virginia Values Act, which went into effect in July 2020. It expands the scope of the Virginia Human Rights Act to prohibit discrimination in employment and housing based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Leeson says when the act was approved, defense attorneys predicted disaster for corporate defendants, while plaintiff’s lawyers were saying, “This is a new day in Virginia and we’re anxious to start filing these claims.” But “lo and behold,” Leeson says, “there have been very few cases” related to the act.

That’s partly because of the timing — the Virginia Values Act took effect during the pandemic — and partly because of the administrative processes the new law includes. This January, Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring created the Office of Civil Rights, which expanded and reorganized his office’s previous Division of Human Rights. Prior to the Virginia Values Act, discrimination claims based on race or gender identity would have been handled exclusively in federal courts. Now there’s a state court option with different rules and an investigation phase that can take months to complete. “There’s probably not a smooth-running machine in trying to process these complaints,” Leeson says. That could push potential litigation even farther down the road, as attorneys for both employers and workers study what the law requires and watch to see how courts respond.

There are plenty of issues that might result in litigation against employers, says Henry Chambers Jr., a professor with the University of Richmond School of Law who teaches constitutional law and employment discrimination. There are vaccine rules, the treatment of remote and in-office workers, and marijuana policies now that recreational marijuana use is legal in Virginia.

Given the social protests related to civil rights that erupted last year following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, Chambers predicts workers returning to the workplace will have “shorter fuses, and they will feel freer to discuss issues in the office” that they previously might have avoided.

“It’s difficult because our workplaces can become kind of our second homes, which can be a plus and a minus,” he says. As people return to commuting and to sharing a workplace again, “there are a whole host of human resources issues that might turn into litigation.”

Compliance confusion

There also continues to be considerable confusion among businesses over pandemic-related state and federal requirements. And providing compliance advice is driving a lot of business for law firms. “It’s been that way the entire time,” says Karen Doner, founding partner of Tysons-based Doner Law, which specializes in employment law and commercial litigation.

Virginia, for example, was the first state to pass a workplace safety standard specific to COVID-19, she says. The Virginia Department of Labor and Industry’s “Final Permanent Standard for Infectious Disease Prevention of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus That Causes COVID-19” went into effect in January. Before that, Virginia employers were expected to operate under a “Temporary Permanent Standard” implemented in July 2020.

Depending on the types of tasks employees perform, state workplace requirements for employers to control and prevent the spread of COVID-19 can include a range of requirements for training, protective equipment, and reporting and notification. Virginia employers failing to comply with the state standard are subject to fines up to $12,726 for serious violations and $127,254 for willful violations.

“Many employers are under the impression that the Final Permanent Standard is no longer in effect, but it is,” Doner says. “It’s troubling that the guidance has not been clearer.”

Additionally, employers who provide health care services or support services must comply with the federal OSHA COVID-19 Emergency Temporary Standard, which went into effect in June.

Employers remain perplexed over which of the layers of state and federal rules apply to them. Mask requirements, for example, have been hard to follow, Doner says, with differing requirements for certain work settings and rule changes from federal, state and local authorities.

With the rising threat of the COVID-19 delta variant interfering with planned returns to offices, employers can count on uncertainty to continue. And for attorneys who guide employers through the changing legal terrain, there is much to learn. The past year is “the most challenged I’ve been in my whole career,” Doner says.

Much of what’s happening now for businesses and their legal counsel is based around preventing legal liability. Jeremy Schneider, principal with the Washington, D.C., office of Jackson Lewis, represents businesses facing workplace litigation, and his firm also conducts corporate trainings to help businesses avoid litigation in a range of areas, such as diversity in hiring related to age, race, gender, religion, sexual orientation or other characteristics unrelated to job performance. “We have a lot of employers asking us to do unconscious bias training,” he says. “Now more than ever, employers need to be vigilant and aware of the problems that can arise.”

As courts work through any legal challenges to the new laws, employment attorneys are paying close attention to how courts are interpreting new laws and regulations. “It’s been fun to watch a new area develop,” says Cunningham with Hunton Andrews Kurth. “There’s a lot of new law being developed right now, so it’s interesting.”

UMW is continuing its push to teach students digital communications skills no matter their field of study, says McClurken. In 2015 the school created a major, communication and digital studies. This year 172 students were pursuing that major with 44 students minoring in the field.

UMW is continuing its push to teach students digital communications skills no matter their field of study, says McClurken. In 2015 the school created a major, communication and digital studies. This year 172 students were pursuing that major with 44 students minoring in the field. Even if UMW doesn’t aim to be a lot bigger, under Paino’s leadership it is going to grow and renovate. And for this modest-size campus, there are many new things planned or underway. In 2016 the school opened its massive University Center, which houses dining facilities and offices of university programs such as the James Farmer Multicultural Center. The former dining center, Seacobeck Hall, will soon be renovated and reopened as home to the school’s College of Education. Plus, renovations are planned or underway in several of the school’s older residence halls.

Even if UMW doesn’t aim to be a lot bigger, under Paino’s leadership it is going to grow and renovate. And for this modest-size campus, there are many new things planned or underway. In 2016 the school opened its massive University Center, which houses dining facilities and offices of university programs such as the James Farmer Multicultural Center. The former dining center, Seacobeck Hall, will soon be renovated and reopened as home to the school’s College of Education. Plus, renovations are planned or underway in several of the school’s older residence halls. The person leading the partners program is Dr. Emily White, who joined the foundation as director of operations in 2016. Besides her training in general surgery — she’s a U.Va. School of Medicine graduate — White also has experience on the business side, having held leadership roles with several startup companies.

The person leading the partners program is Dr. Emily White, who joined the foundation as director of operations in 2016. Besides her training in general surgery — she’s a U.Va. School of Medicine graduate — White also has experience on the business side, having held leadership roles with several startup companies. Wood says electric co-ops are a good match for rural broadband projects. For one, co-ops have been building and maintaining utility infrastructures in rural areas for decades. The same poles that carry electric wires also can carry broadband. “So, it works for us, where it’s more difficult for the investor-owned, private companies,” Wood says.

Wood says electric co-ops are a good match for rural broadband projects. For one, co-ops have been building and maintaining utility infrastructures in rural areas for decades. The same poles that carry electric wires also can carry broadband. “So, it works for us, where it’s more difficult for the investor-owned, private companies,” Wood says. So, VCTA will push for public subsidies that support private-sector expansions into unserved areas. But others say the rural areas have waited long enough. The Virginia Association of Counties (VACo) is joining the discussion. Sherrin C. Alsop, VACo’s president, is a member of the King and Queen County Board of Supervisors. The county grew tired of waiting for private-sector investment, she says. “That’s why we said, if we want it, we’re going to have to do it ourselves.”

So, VCTA will push for public subsidies that support private-sector expansions into unserved areas. But others say the rural areas have waited long enough. The Virginia Association of Counties (VACo) is joining the discussion. Sherrin C. Alsop, VACo’s president, is a member of the King and Queen County Board of Supervisors. The county grew tired of waiting for private-sector investment, she says. “That’s why we said, if we want it, we’re going to have to do it ourselves.” Sunset Digital, the purchaser of the OptiNet system, will get $29.5 million over 10 years from the FCC, says Paul Elswick, the company’s president and CEO. The FCC has long subsidized rural telephone service, and this time the agency is devoting funds from that same funding program to rural broadband, he says.

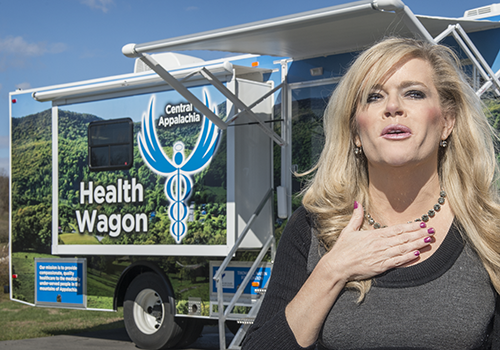

Sunset Digital, the purchaser of the OptiNet system, will get $29.5 million over 10 years from the FCC, says Paul Elswick, the company’s president and CEO. The FCC has long subsidized rural telephone service, and this time the agency is devoting funds from that same funding program to rural broadband, he says. Teresa Gardner Tyson has firsthand knowledge of the needs of the uninsured. She is executive director of The Health Wagon, a nonprofit group that provides health-care services in Southwest Virginia. Because of the large number of uninsured people in the region, she says, “Medicaid expansion would be favorable for the people I treat.” The region, however, needs more doctors and mental-health professionals. “So, anything we can do to put more boots on the ground here in Southwest Virginia is favorable.”

Teresa Gardner Tyson has firsthand knowledge of the needs of the uninsured. She is executive director of The Health Wagon, a nonprofit group that provides health-care services in Southwest Virginia. Because of the large number of uninsured people in the region, she says, “Medicaid expansion would be favorable for the people I treat.” The region, however, needs more doctors and mental-health professionals. “So, anything we can do to put more boots on the ground here in Southwest Virginia is favorable.” The Virginia Community Healthcare Association (VCHA), which has 29 member organizations at 147 sites, serves about 100,000 uninsured people every year. Neal Graham, its CEO, estimates that of that number, about 70,000 would be eligible for Medicaid under expansion. “So, that’s 70,000 people who are currently in our health-care system who would be eligible.” VCHA already is the largest Medicaid provider in the state, Graham says, and after expansion it could wind up enrolling an additional 100,000 new Medicaid patients.

The Virginia Community Healthcare Association (VCHA), which has 29 member organizations at 147 sites, serves about 100,000 uninsured people every year. Neal Graham, its CEO, estimates that of that number, about 70,000 would be eligible for Medicaid under expansion. “So, that’s 70,000 people who are currently in our health-care system who would be eligible.” VCHA already is the largest Medicaid provider in the state, Graham says, and after expansion it could wind up enrolling an additional 100,000 new Medicaid patients. Kay Crane is CEO of Piedmont Access to Health Services, known as PATHS, which has five health centers in Southern Virginia. She says Medicaid expansion would have a good effect on federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), which would receive “enhanced reimbursements” — more money — because of their status. That means they could hire more providers, Crane says.

Kay Crane is CEO of Piedmont Access to Health Services, known as PATHS, which has five health centers in Southern Virginia. She says Medicaid expansion would have a good effect on federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), which would receive “enhanced reimbursements” — more money — because of their status. That means they could hire more providers, Crane says. Barry DuVal, president and CEO of the Virginia Chamber of Commerce, says that when it comes to which strategies are best for improving the Virginia economy, the state’s business community “is the most aligned today than it has ever been in the past 20 years.” The chamber’s Blueprint plan, for example, pushes four main points — marketing the state as a prime business site, expanding broadband access, developing business-ready sites and customizing

Barry DuVal, president and CEO of the Virginia Chamber of Commerce, says that when it comes to which strategies are best for improving the Virginia economy, the state’s business community “is the most aligned today than it has ever been in the past 20 years.” The chamber’s Blueprint plan, for example, pushes four main points — marketing the state as a prime business site, expanding broadband access, developing business-ready sites and customizing  Charles Majors, chairman of the board of Danville-based American National Bankshares, heads the GO Virginia council in the organization’s Region 3. The region, which has a population of 372,000, includes the cities of Danville and Martinsville and 13 counties: Amelia, Brunswick, Buckingham, Charlotte, Cumberland, Halifax, Henry, Lunenburg, Mecklenburg, Nottoway, Patrick, Pittsylvania and Prince Edward.

Charles Majors, chairman of the board of Danville-based American National Bankshares, heads the GO Virginia council in the organization’s Region 3. The region, which has a population of 372,000, includes the cities of Danville and Martinsville and 13 counties: Amelia, Brunswick, Buckingham, Charlotte, Cumberland, Halifax, Henry, Lunenburg, Mecklenburg, Nottoway, Patrick, Pittsylvania and Prince Edward.

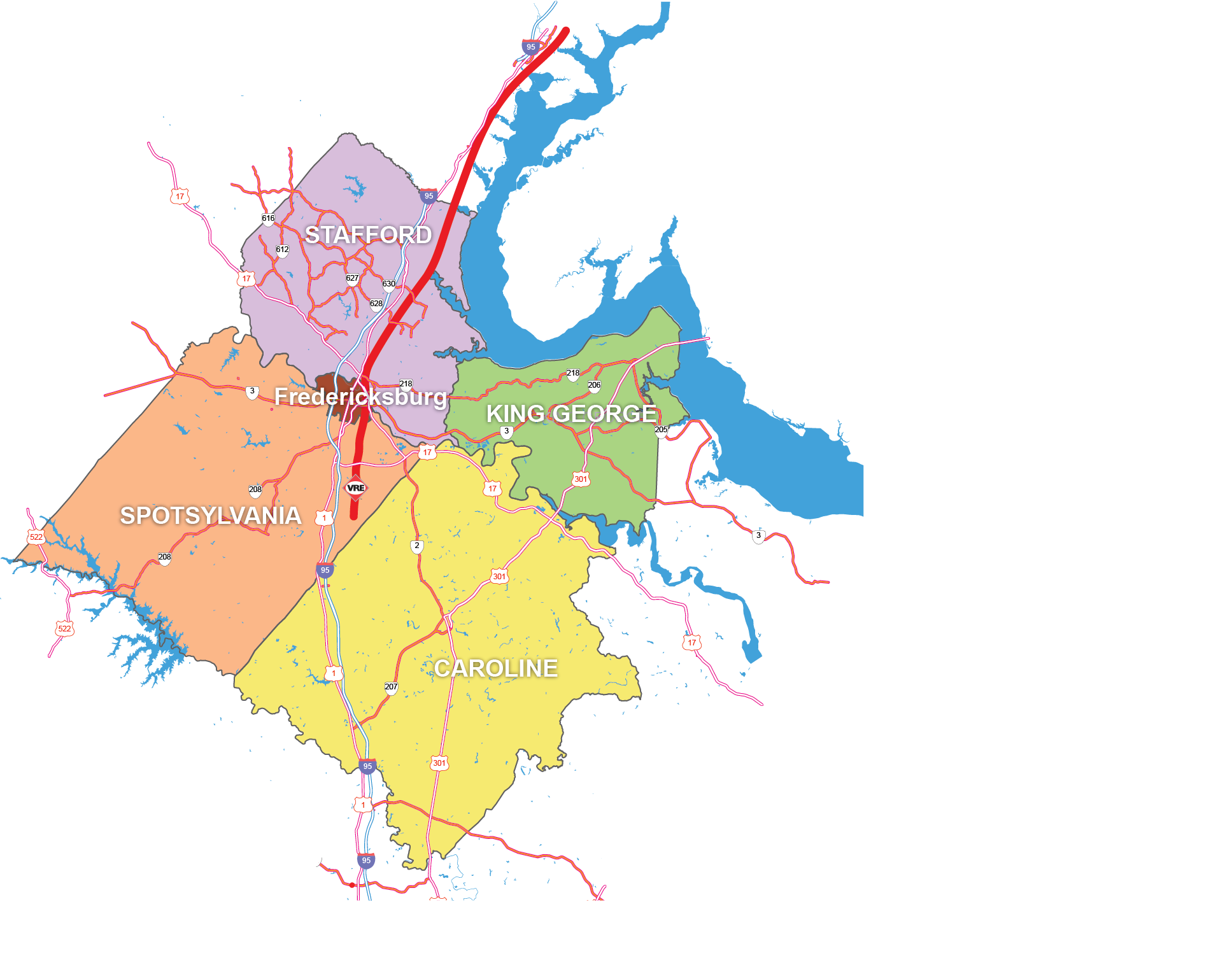

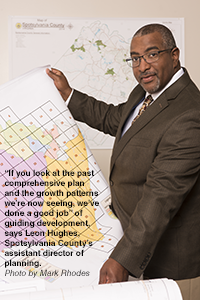

Interstate 95 dominates everything when it comes to development in the region. Spotsylvania’s most active growth is around the interstate exit at mile 126, its northernmost interchange, and that’s what the county wants. “If you look at the past comprehensive plan and the growth patterns we’re now seeing, we’ve done a good job” of guiding development, says Leon Hughes, the county’s assistant director of planning.

Interstate 95 dominates everything when it comes to development in the region. Spotsylvania’s most active growth is around the interstate exit at mile 126, its northernmost interchange, and that’s what the county wants. “If you look at the past comprehensive plan and the growth patterns we’re now seeing, we’ve done a good job” of guiding development, says Leon Hughes, the county’s assistant director of planning. The sense among county planning staff is that many new residents have left parts of the country that have been hurting economically for years. Jacob Pastwik, a planner for Spotsylvania, is from Buffalo, N. Y., and says he’s found a lot of former Buffalo residents here, looking for work.

The sense among county planning staff is that many new residents have left parts of the country that have been hurting economically for years. Jacob Pastwik, a planner for Spotsylvania, is from Buffalo, N. Y., and says he’s found a lot of former Buffalo residents here, looking for work. Also adjacent to the new interchange is a proposed project by Stafford-based Garrett Development. The company has about 1,000 acres on the west side of I-95 and has been seeking county approval for a development called George Washington Village. It’s planned as a mixed-use development that Andy Garrett, the company’s founder and president, says would have 1,200 residential units, including single-family homes, townhouses and apartments, along with commercial space.

Also adjacent to the new interchange is a proposed project by Stafford-based Garrett Development. The company has about 1,000 acres on the west side of I-95 and has been seeking county approval for a development called George Washington Village. It’s planned as a mixed-use development that Andy Garrett, the company’s founder and president, says would have 1,200 residential units, including single-family homes, townhouses and apartments, along with commercial space.